Figure 1. Claremont Canyon in 1935 was mostly grassland and abandoned eucalyptus plantations—many of which still exist today (circled in orange). East is up.

The end of cattle grazing

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the East Bay Hills were largely grasslands as a result of wide-spread cattle grazing. With the establishment of the East Bay Regional Park system in the 1930s, cattle grazing came to an end and the landscape underwent a steady transformation as native coastal scrub expanded into grassland areas. For example, in Tilden, Chabot, and Redwood regional parks, between 1939 and 1997, coastal scrub areas nearly tripled while grassland areas decreased by an average of 69 percent (Russell and McBride, 2003). This transformation meant not only a change in habitat conditions for plants and wildlife but also a change in wildfire hazard of the overall landscape.

Figure 2. This map shows the steep topography of Claremont Canyon with today’s local and regional parks and open spaces shown in green. North is up.

The infamous freeze of 1972

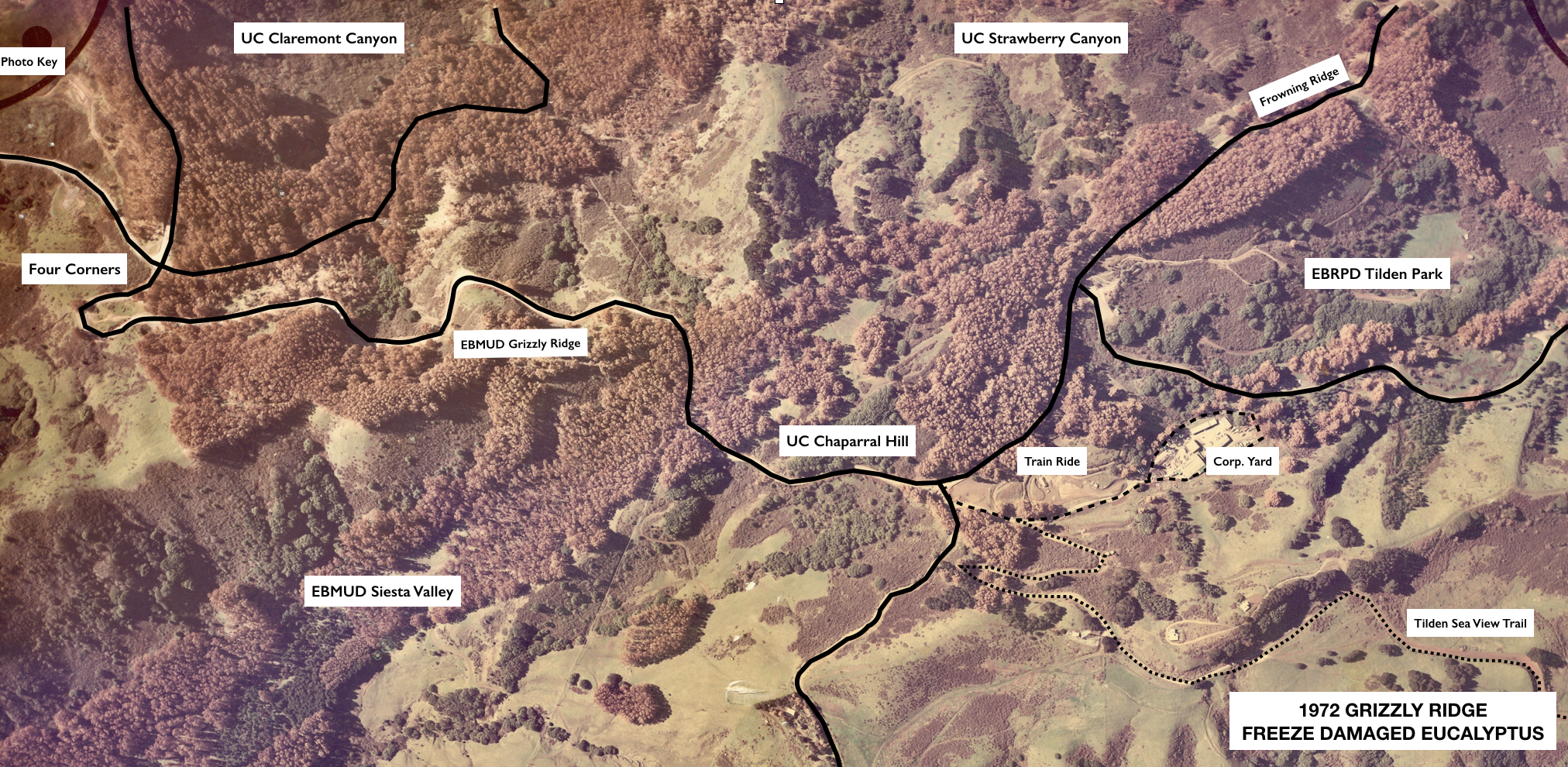

A second major land transformation occurred in 1972 when a prolonged freeze—with eleven days of nighttime temperatures below 30 degrees—damaged thousands of eucalyptus trees in the higher reaches of the East Bay Hills. The trees, mostly in abandoned eucalyptus plantations, appeared dead and standing like so many torches. Local agencies and forestry experts felt they were dealing with a major increase in wildfire hazard and appealed to state and federal agencies for funding to remove the hazard.

Figure 3. Freeze-damaged eucalyptus are clearly visible along Grizzly Ridge in 1972 above Claremont and Strawberry canyons after the freeze (west is up).

In response, Governor Ronald Reagan declared a State of Emergency to make federal funds available for fire hazard reduction work. A federal grant provided the first $1.3 million to the East Bay Regional Park District to create a 25-mile-long fuelbreak between Anthony Chabot Regional Park and Tilden Regional Park. Work began immediately and a fuelbreak was quickly established. In the first year, 400 acres of freeze damaged trees were cleared from Park District land.

Figure 4. Tilden Regional Park and parts of UC Berkeley’s Hill Campus in 1969 before the freeze of 1972.

Figure 5. Tilden Regional Park and parts of UC Berkeley’s Hill Campus in 1974 after eucalyptus removal.

In addition to the $1.3 million federal grant to the Park District, the State of California, EBMUD, the University of California, and PG&E, as well as the cities of Oakland and Berkeley, all contributed resources to deal with the emergency. UC cleared an additional 400 acres in Strawberry and Claremont canyons, EBMUD and PG&E cleared trees along Grizzly Ridge above Claremont Canyon and Siesta Valley, and the cities of Oakland and Berkeley cleared trees from their high ridge properties. Between 1972 and 1979, the various agencies involved with the emergency spent $6.7 million in freeze-related costs.

Figure 6. Dense eucalyptus groves in upper Claremont Canyon and on EBMUD property in 1969 prior to the 1972 Freeze. (East is up. Claremont Avenue runs west-to-east, left of center of the photo. Grizzly Peak Boulevard runs north-to-south, top of photo, before turning west.)

Figure 7. Claremont Canyon and EBMUD property in 1977 after dead and damaged eucalyptus were logged. ( East is up. Claremont Avenue runs west-to-east, left of center of the photo. Grizzly Peak Boulevard runs north-to-south, top of photo, before turning west.) Note Hwy 24 in the top, right corner.

The logging effort utilized no-cost contractors to remove dead and damaged trees, along with branches, bark, leaves, and other flammable debris that fell to the ground. Usable tree material was transported to Crown Zellerbach Corporation in Antioch where it was chipped and used in paper production.

Unfortunately, during the no-cost contracts, stumps were not treated with herbicide and soon began sprouting new growth from their epicormic buds. Despite early attempts at “sucker bashing,” within a few years new stems—typically four-to-seven per stump—grew into tall, dense canopies. Dry leaves, branches, and long strands of bark began to accumulate under the coppiced groves turning them into a more dangerous fire hazard than ever before.

More than forty years have passed since the aftermath of the freeze, with only sporadic, and often thwarted, attempts to deal with the coppiced eucalyptus. (An article summarizing tree removal work done after the 1970s is coming soon.) Thus, the problem of the damaged, coppiced trees remains today and the threat of wildfire continues to be extraordinarily high. CalFire has designated the East Bay Hills as a very high hazard severity zone.

Landowning agencies in the East Bay Hills all have vegetation management policies stated clearly in their master plans. These policies specify removal of high elevation, coppiced eucalyptus groves to be replaced by naturally occurring native vegetation. The Conservancy urges all landowning agencies to adhere to their own published policies before the next major wildfire moves through our hills.

***

| Table 1. Eucalyptus freeze costs | |

|---|---|

| ____________________________ | ______________ |

| Work during 1972-1973* | $COST |

| ____________________________ | ______________ |

| EBRPD (HUD money) | 1,338,000 |

| City of Berkeley | 17,000 |

| PG&E | 10,000 | State of California | 900,000 |

| UC Berkeley | 248,200 |

| CCC Public Works | 240,000 |

| EBMUD | 1,000,000 | SUBTOTAL | 3,753,200 |

| ____________________________ | ______________ |

| EBRPD follow-up through 1979** | 3,000,000 |

| ____________________________ | ______________ |

| TOTAL | 6,753,200 |

| _______________________________ | ______________ |

| *Trudeau Memo 9/11/73 | |

| **15-member euc crew plus goat grazing | |

Jerry Kent, retired Assistant Manager for Operations at the East Bay Regional Park District, collects digital versions of photos, maps, papers, and articles pertaining to parks and open spaces in the East Bay Hills. He maintains about 33,000 digital documents, many taken during his tenure at the District between 1962 and 2004. Aerial photos were taken by the Navy in 1935 for the National Park Service, which planned the Park District’s first parks between Lake Chabot and Wildcat Canyon. Printed copies are stored in the NPS archives and Jerry made digital copies around 1990. Jerry says, “It’s always safe to attribute photos that I use to the EBRPD Archives where they will all go when I 'wrap it up.”